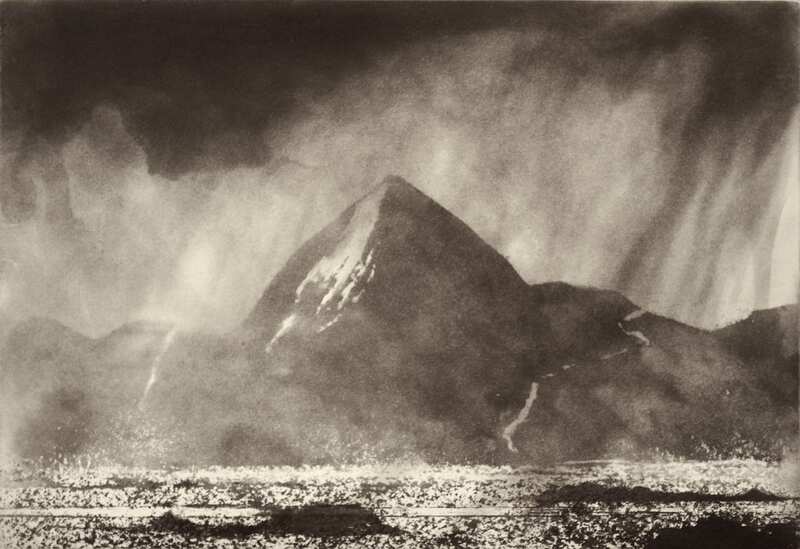

This brilliant piece of painting is by a long time friend, Paul Hempton, 'Across a Ravine' was painted in the early 80's and resides in the Wolverhampton Art Gallery. I have known Paul for fifty years, since his Royal College days. Distant memory of him disappearing through London traffic with his guitar on the way to a band practice. Then a good night in a Yates Wine Lodge in Nottingham, where he had a Fellowship, a string quartet playing on the mezzanine. Later it was the Cotswolds, they had moved to Minchinhampton, I was still working for Ralph Brown and living in Hoskin's studio in Siddington. Then Porlock, Paul had bought a camper van to enable painting expeditions, children had arrived for both of us and life moved on. Paul took a lecturing post in Painting at Wolverhampton Art College. Paul's painting attracted attention, works travelling to shows at home and abroad, and his prints received acclaim, the British Council acquired works, the Victoria and Albert assisted museums with purchases, a trajectory was developing . I have a great watercolour from a show in Nottingham and a later, larger etching, 'Stone, Staff and Ellipse' from 1986. These works give great pleasure but I also have a great collection of Paul's woodcuts, every year for as long as I can remember we have received as a Christmas greeting a fine small woodcut, whose arrival is always much anticipated and appreciated. I have lost sight of Paul's painting and I have a suspicion he has laid down his brushes. We had a pre covid catch up day in Gloucestershire last summer and I entirely lacked the bottle to inquire about the painting, however we had a conversation that perhaps cast, with hindsight, a little insight. Paul has enjoyed, enjoys, fiddling with and fixing their motor vehicles. I failed to comprehend the pleasure that was derived and Paul explained that with mechanical problems there was usually a right way to proceed, a logical solution to be found and an odds on successful outcome, with painting there was always compromise and rarely an absolute, he could be right but I never perceived his work to be unresolved, I felt he always hit the mark, producing some remarkable work. This is a postscript to the above piece, for I have posed the question and my assumptions were entirely wrong, the paint brushes have not been laid down, life continues thank goodness. I would love to publish Paul's response but it would be a be a step too far, however I am truly happy to say that the acerbic wit and withering observations unleashed are an absolute joy.

0 Comments

As an indulged only child my great joy in my early teenage years was a subscription to Studio International. It's monthly arrival was much anticipated, the glossy world of contempory art slapped through the letterbox of my parent's suburban semi and my small world exploded with sophisticated imagery, criticism I struggled to decipher, reviews of London shows and New York exhibitions, interviews with artists hereto unheard of. It triggered in me a striving, a struggle that has persisted unresolved to this day. Many of it's pages are as fresh to me now as they were when first seen on my formica topped kitchen table, and the work of many artists which puzzled and perplexed my too receptive mind, linger on even now. Many of these artists first glimpsed in the Studio grew in stature and have remained a constant touchstone, Ivor Abrahams's Red Ridind Hood was a revelation, and his work still informs me, Brett Whiteley's painting at that time intrigued but his flame didn't sustain, way lost I fear. The Studio brought me to Hubert Dalwood, he did not become a lifelong companion but his 1962 sculpture " O.A.S. Assassins" was to me, as a flailing young art student, inspirational. The O.A.S. was a French paramilitary organisation dedicated to maintaining French colonial rule in Algeria. During the 1950's and early 60's they carried out bombings and assassinations in Algeria and mainland France, their exploits brought France close to the brink of political chaos. Their regime of terror was closely followed by the right wing British press, my father's newspaper occupied a place on the breakfast table so I was only too aware of the terror stalking France. The Dalwood sculpture was a very traditionally crafted 'lump', cast in aluminium , painted and pierced with a ribbon, but with it's sliced drum form, inscription and medal it seemed to resonate with the problems modern France was suffering with the end of Empire and white supremacy. A tombstone for the times, I felt it quite compelling and with it's overt political message, albeit veiled in the whimsy that haunted much of Dalwood's work, it struck as something quite new and refreshing. Dalwood also made a contribution in terms of materials, in the early 60's bronze was still king and lost wax still the preferred casting technique. Dalwood made dirty industrial aluminium respectable and sand casting the way forward. Producing multiple editions in metal became affordable, and the medium, as I was later to find out, was incredibly versatile and would allow a miriad of finishes.

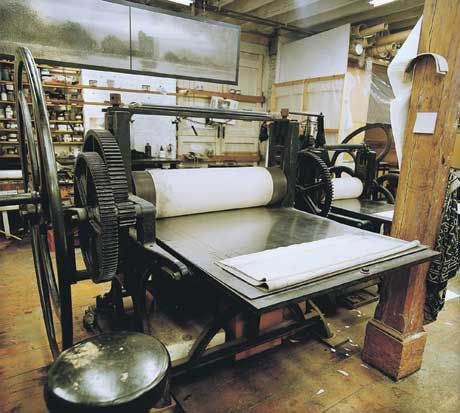

In lockdown, out of lockdown, masks on, masks off, spikes here, spikes there, it's getting really tedious! We had felt reasonably secure in our unfashionable region of rural France and then the Parisiens came to kill off their elderly relatives and claim their covid inheritance. Now the British tourists and second home owners are arriving to spread the pestilence. The locals view them in much the same way they did the German army of occupation, the annual boost to the local economy is unusually far from their thoughts. Unable and unwilling to cross the Channel, I have been compensated with an abundance of photographs and tales of family excursions, extensive coverage of the South West, Somerset, Exmoor, Devon and Dartmoor. Much of this of course is home ground and some of it still sorely missed. During isolation these missives were both a joy and a poignant reminder of happier, less complicated times. With a looming lockdown birthday I thought I would use this moment to garner a little piece of that glorious landscape. I trawled, but could find nothing to fill my eye until Norman Ackroyd hove into view, it wouldn't be Somerset or Devon, I settled for Wiltshire where I lived way back in the seventies. Norman Ackroyd is a brilliant draughstman and fine watercolourist but above all he is a printmaker par excellence, etchings that take your breath, every image a masterclass. The art world teams with nuggets, the sculptor Kenneth Armitage worked on a great sculpture stand he dragged from the studio of Jacob Epstein. Norman Ackroyd produces his large etchings on a press built by Hughes and Kimber in London's East End for Frank Brangwyn in 1900, another great master of the copper plate, lineage or what. So here I sit in the blistering sun waiting for my piece of Wiltshire to arrive, and the pleasure of hanging an Ackroyd. A Houseman moment I think. Into my heart an air that kills

From yon far country blows What are those blue remembered hills What spires, what farms are those? That is the land of lost content, I see it shining plain, The happy highways where I went And cannot come again. |

BOB WESTLEY

AGED AND AWKWARD

[email protected] Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed