|

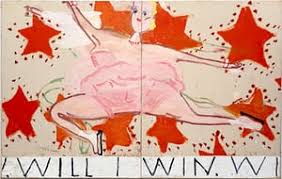

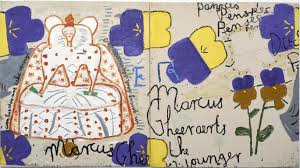

This is not what was planned for this morning, I got waylaid. In my neck of rural France all things remotely agricultural happen in time honoured custom and strictly by the calendar. Trees are felled in the second week of the first month, pruning, the fourth week of the second month, tilling, the second week of the third month and muck spreading during the third week of the fourth month, which is where we are now. This morning was glorious, early morning bread run down hot country lanes with the top down, then I was waylaid. The muck was being spread, a huge machine was trundling a field, hurtling it's evil load across the land and the highway, noxious fumes filled the morning air as I breaknecked my escape. In the square, outside the boulangerie, I planned a more circuitous route home. The sun still beat down and I reflected that the nausea that had swept over me was a minor discomfort compared with that which must wash over London art lovers now the Rose Wylie show has hit town.

0 Comments

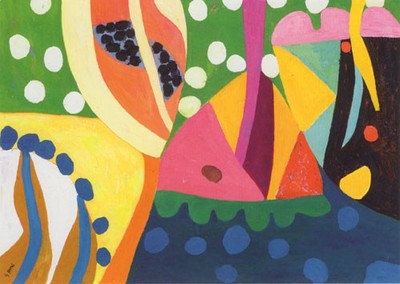

I shall have to stop with this sense of place thing or I will next be banging on Mr Constable's door, heaven forfend. Before I desist I have been reminded of one of our finest painters of place, Peter Lanyon. The paintings that take us away are these, the glider paintings, internationally acclaimed, exuberant, breath taking sweeps of colour and energy. Immediately and mistakenly America looms, but it's only in that Lanyon had seen the American freedoms and observed some new technical possibilities. The artist most called on is de Kooning and Lanyon will surely have seen de Kooning's brushwork and overlayering of pigments but the two artists understanding of place and landscape are fundamentaly different. Lanyon is and was considered a difficult artist, at once topographical yet mythical, representational but historical. When he broke free from the imposed Cornish yoke and achieved international recognition there is a falling away but the pressure to produce for an international market place was immense. The groundbreaking landscape 'Porthleven', in the Tate collection took over twelve months to complete, this kind of timetable was not available with a clutch of clamouring dealers in tow. Lanyon was considered a difficult painter as much of his work was hard to decipher and get into and this was because of it's intellectual complexity. He was also in the early day's producing painting that was considered 'abstract' in appearance when abstraction was viewed with great suspicion and landscape painting seemed out of step with current trends. Lanyon made landscapes where real places, imagination,the human body could be amalgamated into one consummate image. Before beginning a work Lanyon would come to an understanding with the place, he would hope to know it intimately. Maps would be studied, maps made, drawing, note taking while walking the places, cycling, driving and ultimately flying over them. The work could embrace the terrain, buildings, beliefs, legends, the weather, the seasons. John Berger concluded of Lanyon's work that it was little concerned with the appearance of landscape but with it's intrinsic properties. Works like 'Bojewyan Farm 1952 and Trevalgan 1951, above, are both compounds of many sights and different viewpoints. Images of landscape have become sensory revelations of place. He has transcended landscape and through the meld of memory, sensation and information produces a sense of an environment which is subject to constant change and flux. Lanyon described himself as 'a provincial landscape painter', a modest claim made by a man who is one of the most original painters of the twentieth century, his landscape paintings are without precedent, he is a consummate artist.

|

BOB WESTLEY

AGED AND AWKWARD

[email protected] Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed